BIBLE CHRONOLOGY

If it we accept that the leading figures in the Bible were in no way different from their contemporaries, it seems obvious that the most reliable criterion for studying the Pentateuch chronology is that based on the genealogy of those biblical characters; such a criterion is objective, verifiable and cannot be manipulated. It also offers the advantage of not requiring any interpretative effort, since we can accept the biblical text literally while heeding the warning regarding numbers.

The genealogies of the Pentateuch are always given in a "casual" manner and only for the purpose of identifying the person in question. No attempts to legalise any eventual title or other pretensions have been made. They are invariably brief, often repeated several times, and, therefore, have to be considered quite reliable. Also, the genealogies listed in the Books of Samuel appear to be reliable, in particular that of Samuel himself and of Saul and David. These are confirmed in other Books, for example in Ruth, regarding David (Ruth 4,18-22).

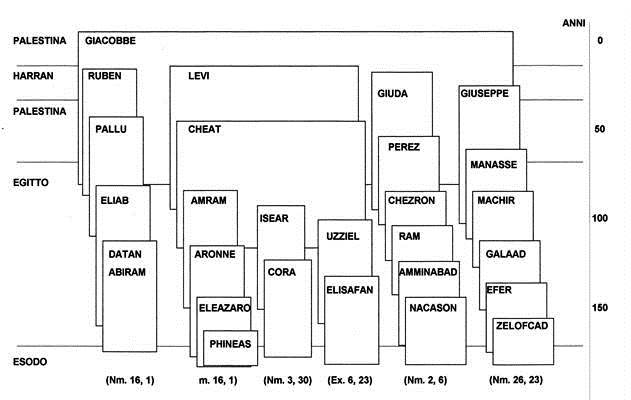

The most numerous, and also the most accurate, genealogies are those referring to the leading figures of the Exodus, in particular the Levites. Aaron was the firstborn son of Amram and Jochebed; Amram was the firstborn of Kohath, he being the second son of Levi, son of Jacob. Jochebed, however, was the daughter of that same Levi and had married the "grandson" Amram, following the custom of marriages between blood-relations. Other similar genealogies are given for various people who had leading roles in the Exodus, such as Korah, Dathan and Abiram (Num. 16,1), the daughters of Zelophehad (Num. 27,1) and so on (see fig. 1 table).

Genealogies are normally given independently and in different contexts, one by one as the various figures come onto the scene. There is no reason, therefore, why the compiler should have made cross-checks and modified the lists handed down to him, simply to render them coherent. This coherency, however, is absolute in the sense that persons belonging to generations too distant from each other are never found together. All the people whose "family trees" are shown and who have contact with each other always occupy parallel positions in the list. In those cases where they belong to different generations, the difference in their ages is evident. Hundreds of people appear in the Pentateuch, yet not one single genealogical error is to be found. No people are actors in an epoch different to the one in which they should appear based on their true family tree.

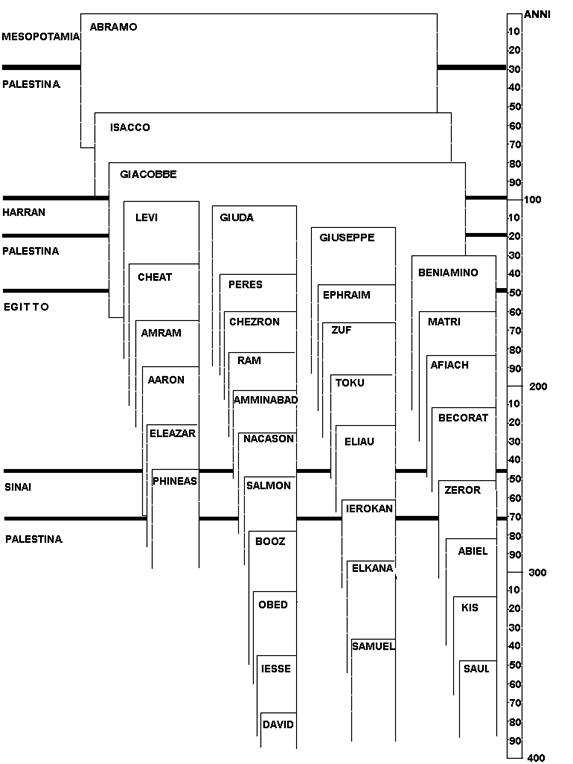

The genealogical lists, therefore, can be used to reconstruct Pentateuch times, by considering the generations in the same way as the growth-rings of tree-trunks (see fig. 2). By connecting together different genealogical lists in which the same persons appear, complete and reliable sequences from Abraham to the kings of Israel (the existence of whom can be accepted without reservation and dated with sufficient reliability), can be obtained.

Obviously, this method cannot guarantee absolute precision; but, if the genealogical sequences are not excessively long, any possible errors are sufficiently bounded and in any case do not exceed a few decades. This criterion, therefore, is quite sufficient to set with reasonable certainty the historical period in which the biblical events occur. On this basis then, we can determine relatively simply the period in which certain biblical events took place, solely by making use of the data furnished in the Bible itself.

First, let us try to ascertain the Exodus epoch since this is the central episode of the Pentateuch. We can base the calculation upon the genealogy of David since it is sufficiently complete and reliable. It is listed for the first time in the Book of Ruth (4,18-22), great-grandmother of the king, and confirmed in successive Books.

From this list we learn that eleven generations separate Jacob's son Judah, and David. An important figure mentioned in the list is Nahshon, son of Amminadab, who played a key role in the events of the Exodus. In fact he was nominated Commander of Judah's troops (Num. 2,3) immediately after the first census conducted by Moses at the foot of the Holy Mount, "on the first day of the second month of the second year after the Israelites came out of Egypt" (Num. 1,1). He was also a brother-in-law to Aaron who had married his sister Elisheba. Considering that such an appointment required a man of mature nature with an authoritative bearing--but not too old since he would have to be in the forefront fighting beside his men--Nahshon must have been about forty.

Salmon, son of Nahshon but not specified as his first-born, was perhaps born in the Sinai desert and at the time of the Palestine conquest was no more than a young boy. His son Boaz, as portrayed in the Book of Ruth (Ruth 3,7), was well-off and authoritative, but so calm and staid that he was inclined to doze off at times. When he married Ruth he was probably middle-aged, perhaps over fifty. Ruth gave him a son, Obed, who fathered Jesse (it is not known whether he was an only son or one of many). David was Jesse's eighth male child (1 Sam. 16,10), born, therefore, when his father was well on in years. Solomon entered the world when his father David was no longer young (1 Sam. 12,24).

On the basis of these considerations we can calculate fairly approximately that between the Exodus and the birth of Solomon, a little more than two hundred years passed. Since we are reasonably certain that Solomon was born about 1000 B.C., we can calculate with equal certainty that the Exodus took place around the end of the 13th century B.C. We can arrive at the same conclusion on the basis of the genealogies of Saul and Samuel.

Having established the period in which it occurred, we can more precisely fix the date of the Exodus by making full use of the frequent and numerous references in the Bible itself. In the 13th century B.C. Egypt was ruled by only two Pharaohs: Rameses II, who reigned for no less than sixty-six years, and his son Merenphthah, who held the throne for a further twenty years. The last rulers of the 19th Dynasty were quite insignificant, reigning for very short periods over an Egypt which was in total chaos. This makes the task to identify the rulers mentioned in Exodus sure and simple since the Bible refers only to two. The first used the Jews as an unskilled labor force to help build the cities of Pithom and Pi-Rameses. This same Pharaoh persecuted Moses, forcing him to flee to the Sinai where he found refuge with Jethro the Midianite. There seems no doubt that he was Rameses II and in any case this conclusion is consistent with a long and well-founded tradition.

We read in Exodus 2,23 that following the death of the Pharaoh who had persecuted him (i.e. Rameses), Moses returned to Egypt and together with Aaron began at once to organize the flight of the Israelites from Egypt. Because of its general complexity and slow pace of establishing the necessary contacts, the organisation of the whole enterprise must have required a period of not less than two or three years. The Jews took forty-four days (Num. 33,3; Ex. 19,1) to go from Pi-Rameses to Mount Sinai and remained there for just less than a year (Num. 10,11).

A few weeks after their departure from Sinai, as soon as Joshua had returned from his reconnaissance mission in Palestine, the Jews suffered a serious defeat at the hands of the Canaanites near Kadesh-Barnea (Num. 14,15; Deut. 1,44). By an extraordinary coincidence, there is a similar historical account in the "Stele of Israel", so-called because for the first time in history the name "Israel" appears. In this stele Merenphthah celebrates victories gained over the Libyans, who, in the fourth year of his reign had invaded the Nile Delta. On the same stele there is a list of victories over rebel populations in Palestine, which then was still part of the Egyptian Empire. Merenphthah almost certainly never left Egypt and, therefore, these victories were clearly gained by his generals or by populations subject to him, such as the Canaanites[1] (8). The victory over Israel occurred in the fifth year of Merenphthah's reign; since the Jews had left Egypt less than eighteen months before this, the Exodus must have happened in the fourth or at the end of the third year of Merenphthah's reign.

Let us open a book of ancient History and find out when Rameses and Merenphthah reigned. Unfortunately, we find contrasting dates for Rameses' death; J. A. Wilson, an American historian, gives it as 1238 B.C.; the Cambridge school puts it at 1224, while A. Kitchen claims it is 1213. There is a difference of 25 years among these. It is important to note that the exact date of Rameses' death is one of these three and not any intermediate year among the twenty-five [2]. The Exodus of the Jews from Egypt, therefore, must have taken place either in 1235, in 1221, or even in 1210 B.C. The calculations made on the basis of David's genealogy would tend to favor the last of these three figures; but in any case the difference is not so great as to exclude the other two.

But instead of pinning our faith on absolute dates which give wide margins of uncertainty, it is preferable to latch onto Egyptian chronology by referring to the reigns of the Pharaohs in years. The date of the Exodus, therefore, can be set with reasonable certainty in the fourth year of Merenphthah's reign. This result is important because it is possible, by starting from this date, to link it with the entire Pentateuch chronology. This is especially true considering the Patriarchs, because the Egyptian chronology during their period is quite precise and reliable.

The number of generations stretching between Abraham and the Exodus is limited and has been confirmed time and again by numerous and differing sources. Furthermore, the passages indicating the ages of various characters vis-à-vis the events in which they took part are numerous and precise enough to allow us to reconstruct the dates of those events with reasonable reliability.

We can initially establish the epoch when Abraham lived, from a brief study of the events that occurred between Abraham and the Exodus. When Sarah, wife and sister of Abraham (Gen. 20,12), reached Palestine, she was in the prime of youth and was very beautiful and desirable. She gave birth to her one and only child twenty-five years later, when she had ceased menstruating having just reached menopause, say at forty-five (Gen. 18,11). Abraham was ten years older (Gen. 17,17), and, therefore, about fifty-five.

Isaac may have married late for those times, but in any case Esau and Jacob must have been born before he was thirty. When Jacob was about twenty he went back to Mesopotamia where he married two of his cousins, together with her handmaid, and with whom he fathered twelve children in rapid succession.

Of these children, Levi was the one whose descendants played major roles in the events of Exodus. When he was born, in Haran, his father could not have been more than thirty. Jacob then returned to Palestine with all his family when he was forty (Gen. 31,41). It was there that Levi married and had children, the second of whom was called Kohath. When Kohath was born Levi could have been about thirty. His grandfather, Jacob, moved to Egypt before Kohath grew to be adult. Kohath’s first child was Amram, born in Egypt, and his first-born was the Aaron destined to play a major role in the Exodus. When he left Egypt, Aaron was already a grandfather since his third son, Eleazar, had fathered Phinehas (Ex. 6,14-27; Num. 26,58-60; etc.).

fig. 1

Correctly working out the figures shows that Abraham set out from Haran for Palestine about two hundred and thirty years before the Exodus, with a margin of error of not more than twenty years. He was born, therefore, in the first half of the 15th century, or at the earliest at the end of the 16th when the 18th Dynasty reigned in Egypt.

The same result can be obtained on the basis of the genealogy of any one of the persons in the Pentateuch (see table and figs. 1, 2). The historical period in which Abraham lived can, therefore, be given conclusively; if one suggests any dates prior to this, as is the present-day tendency, the Bible's account is thereby disarticulated and its credibility destroyed.

fig. 2

[1] E.Bresciani, "Letterature e Poesia dell'antico Egitto", Einaudi, Torino 1969, p.277. From the "stele of Israel": <<A great joy occurred to Egypt, exultation come out of the town of Tomeri; they tell about the victory that Merenphtah won against the Lybians (...). The kings are overthrown and they said Salam! Nobody between the Nine Arches is holding his head up; Lybia is wretched; Kheta is pacified; Cannan is spoiled with great ravages; Ascalon is deported; Geser is conquered; Ionoam is completely destroyed; Israel is desolate, his seed no longer exists. Palestine is now a widow for Egypt. All countries are pacified, all people who were turbulent were enchained by king Merenphtah, be he alive like Ra, every day>>.

[2] . F: Cimmino, "Ramesses II il Grande", Rusconi, Milan 1984, p.320. <<Contrary to our calendar, which reckons the years beginning from a date zero, that is, from the birth of Jesus Christ, the Egyptian calendar appears to be not very useful were chronological history is concerned. The Egyptians reckoned the years separately for each Pharaoh; thus we know that a given event happened during a certain year of the reign of that Pharaoh. But we do not have a certain and reliable list of the successions to the throne, so very often we do not have a comprehensive vision of Egyptian history, but only a fragmentary and blanks-pocked vision of the events that happened during the reign of a given sovereign. Where the reign of Ramesses II is concerned, scholars are uncertain about the date of coronation which occurred either in 1290 or in 1304 b.C. The calculation of this is very complicated and was effected on the base of a lunar date, that refers to the 52nd year of the Pharaoh's reign, and of some cuneiform texts coming from the kingdoms of Near East. In spite of very accurate studies, it is hard to adopt a definite position in this matter, that only further discoveries will be able to clarify.>>