An ancient Christian pilgrimage

to Har Karkom–Mount Sinai

Summary: - The paper shows that Har Karkom was known as the biblical Mount Sinai by Christian pilgrims of the first four centuries C.E. Evidence is provided by a manuscript found in 1884 in the Tuscan town of Arezzo, with the diary kept by a Christian pilgrim, named Egeria, who at the end of the IV century made a trip to the mountain of Moses. Immediately the scholars decided that the account was referred to St Katherine, but unfortunately the description, very accurate and detailed, does not fit at all the reality of that mountain, perhaps apart a single match at the end of the visit. The described distances, travel times and description of the environment are unsuitable to the area of Santa Catherina in a macroscopic way. Besides, the pilgrim reports the existence of monks’ communities and agricultural sites both on the mountain and in the surrounding valley, including dwellings and churches which, according to the archaeological evidence, did not exist there at that time.

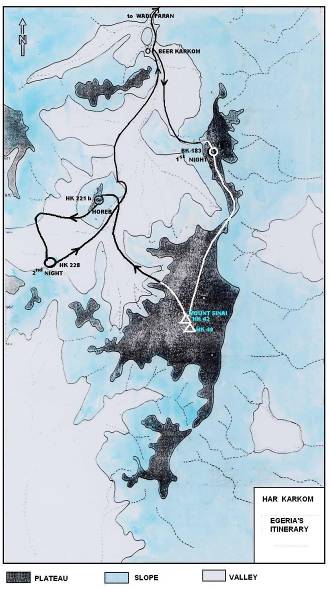

In all evidence the account is referring to a different location. Through an accurate survey at Har Karkom, however, it becomes plausible that the narrative refers to a journey made on that precise area. If we strictly follow the indications of the manuscript, starting from the very point where the pilgrim looked out from a gorge over the God’s valley, we are then taken along an itinerary completely matching, down to the smallest detail, the information provided by the diary, at the point that it could be regarded as the best guide ever to a biblical tour of Har Karkom.

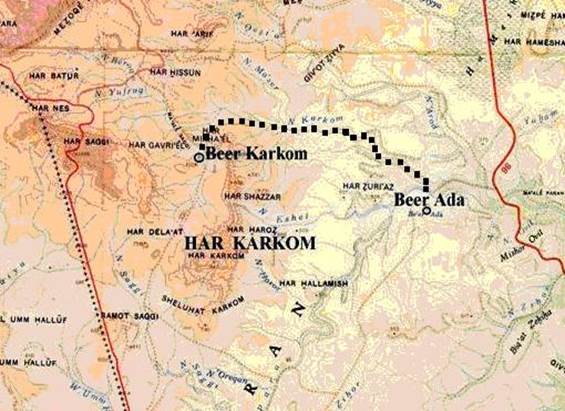

fig. 1 - The area of Har Karkom is situated at the extreme south-west border of the Nabatean kingdom, known as Arabia at the time of Rome, with Avdat about 40 km to the North and Petra the same distance East

Sinai, a Nabatean mountain

An interesting outcome of the archeological discoveries at Har Karkom is that this mountain was known as the biblical Sinai since the beginning of the Christian era. As a matter of fact, 30% of its 1200 archaeological sites belong to the roman-byzantine epoch and in all probability they were due to communities of monks, who thrived there until the beginning of the 7th century, when they were swept away by the Islamic invasion.

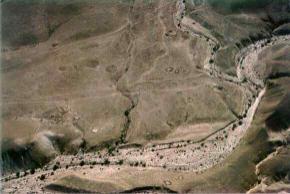

fig. 2 – A settlement of roman-byzantine monks (site BK506) in Karkom valley, with eight cells ranged along the wadi (the round structure on the right belongs to the Bronze Age period)

St. Paul, in his letter to the Galatians, says that soon after his conversion in Damascus he went for “three years to Arabia”, that is the kingdom of the Nabateans, adding after a few rows that “Sinai is a mountain of Arabia” (4, 25), within which borders there is Har Karkom.

The existence of monks, more precisely ebionites[1], in that area is testified by Epiphanius, who in his book “Panarion” (30, 18, 1 & 29, 7 7-8), written on 375, says that they were spread over most of the provinces of the Nabataean Arabia. His words were confirmed a few years later by a Roman pilgrim, Egeria (381-384), who in his diary described communities of monks in Transjordan, as well as around and on top of the God’s mountain.

In the following pages we will show that this mountain was not the St. Katherine, but Har Karkom, that fits entirely the pilgrim’s description.

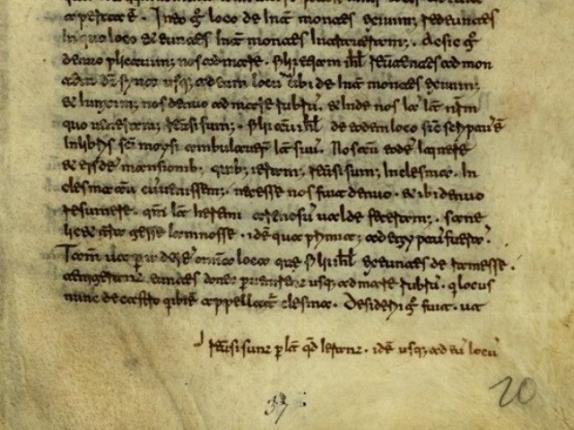

The Codex Aretinus

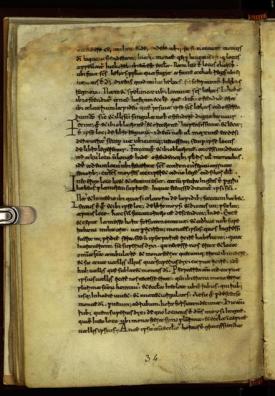

Egeria’s diary was discovered on 1884 in Arezzo, Tuscany, and it’s written on a parchment called Codex Aretinus 405, produced between 1087 and 1105 in the monastery of Monte Cassino. [2]

fig. 3 - Two pages of the Codex Aretinus 405, with the diary of Egeria’s pilgrimage

to the Mount of God.

The initial, the final and four intermediate pages of the manuscript are missing. No other copies of the diary have been found so far, but precious information about the content of the missing parts is contained in a letter, written around 680 by a monk named Valerius to his brothers of Bierzo’s monastery, in Galicia, Spain, in which he makes a list of the mountains climbed by the pilgrim and of the biblical sites that she visited.

Egeria’s pilgrimage to the Holy Land took place between 381 and 384 and the visit to the mountain of God is supposed to have been made at the end of 383.

Unanimously the scholars agreed that the mountain visited by the Roman pilgrim had to be identified with the St Katherine massif, in the southern part of the Sinai Peninsula, which the Christian tradition blessed as the biblical Sinai since the beginning of the sixth century (the very first mention of it as a possible biblical Sinai is made by Procopius, historian at the court of emperor Justinian).

A survey made on 1899 by M. J. Lagrange , trying to identify on the St Katherine an itinerary somehow fitting the narrative of the manuscript, failed to demonstrate a close match with it, to the point that 90 years later another scholar, Franca Mian, made a second attempt, proposing a few alternatives, with the same disappointing result.

Mount Sinai in Egeria’s description

Egeria’s account is very precise, detailed, clear and direct to the point that it does not make room to any personal interpretation. She portrays the territory in a photographic manner, describing the form and position of the mountains, the form and dimensions of the valley, the precise distances and travel times from one point to the other. She describes what she sees near the path she walks along, relating everything to the biblical text: tombs, churches, caves, ancient encampments, dwellings, altars and so on. All real elements that should be easily verified by a survey on the concerned area.

She reports her own activities with precision and coherence, her movements, the precise time of every activity, and her encounters with monks who lived upon the mountain and in the surrounding valley.

These information allow us to draw a precise outline of Egeria’s visit to the holy mountain.

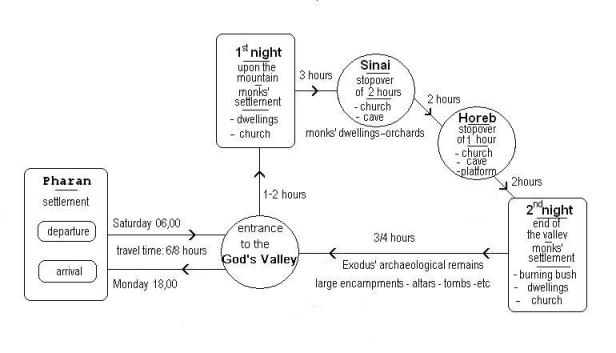

fig. 4 – A synthetic outline of the visit made by Egeria to the God’s Mountain, with travel times and other elements described in her diary.

Dimensions of the God’s valley and distances

In Egeria’s account the valley’s dimensions and the distances between key points are reported with precision:

- four miles from the entrance of the valley to the mountain (§1,2 of the manuscript),

- sixteen thousand footsteps the length of the valley and four thousand footsteps its width (§2,1);

- three miles from the top of Mount Horeb to the site of the burning bush (§ 4,5);

- thirty five miles from Faran to the mountain of God (§ 6,1).

These are important information and therefore it is essential to understand what they really mean. The Romans, when marching their armies through Europe, used the unit of long distance mille passuum (literally "a thousand paces"), corresponding to about 1,480 meters (1,620 yards), because each pace or stride was two steps. If this was the unit of length used by Egeria, then the distances reported in her account were respectively of 6, 24, 4.5 and 52 km.

Egeria, however, is keen to point out that those measures were told to her by the local guides, ignorant monks who almost certainly were not familiar with the Roman army practices. For them distances had to be expressed in simple footsteps, of about 70 cm each, and therefore those values go down to 3, 12 , 2.2 and 26 km. Besides, those distances were measured along the paths and therefore they were a little bit longer than the distances as the crows fly. Let’s say a 10 % longer.

In the first case the dimensions of the God’s valley were of 22 km by 5, hugely out of scale in the St Katherine scenario. In the second and more probable case, these dimensions are reduced to 11 by 2.5 km, still at least three times longer than the real ones.

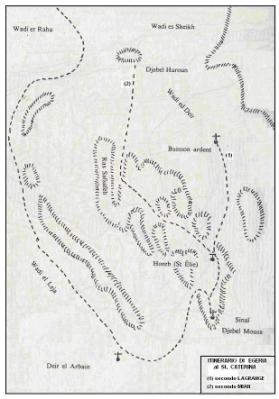

Surprisingly the distance from the God’s mountain to Feiran (and only this) is correct if it was expressed in Roman miles (while is half of its real value if expressed in normal footsteps). A part this lonely match, in both cases the dimensions of the God’s valley, as reported by Egeria’s diary, are macroscopically wrong in the St. Katherine’s scenario, as can be seen in the following map.

fig. 6 – The God’s valley as it is seen from the St Katherine monastery. At the center of the picture, the gorge from which Egeria looked out to the valley for the first time. It’s beyond comprehension why she decided to make a long detour amongst the mountains, instead of going directly to the monastery.

Maps and pictures show that there is no match between Egeria’s account and the geography of the St. Katherine, with the only exception of the distance from Feiran to that mountain (which in any case could not have been covered in one day only, as we understand from the manuscript).

fig. 7 – Egeria’s itinerary in the St Katherine scenario, according to Lagrange and Mian. In the small square on the right the tour made by the pilgrim around and on top of the mountain.

A manipulated account

A large part of Egeria’s account is dedicated to encounters with several monks who lived in that area, and to describe churches, agricultural sites, both upon the mountain near its top and in the surrounding valley, archaeological remnants, attributed to the exodus’ Jews, and so on.

Nothing of this kind existed in the St. Katherine area at Egeria’s time. We can therefore state with certainty that her account is related to a different mountain.

There are, however, two data that look correct in the St. Katherine scenario: the declared distance from Faran to the God’s mountain is the same as that from Feiran to the Gebel Musa (if we suppose that it was expressed in Roman miles), and the fact that Egeria, according to the manuscript, went on on her trip following backward the legs of the Jews’ exodus, undoubtedly starting from Feiran, because two days later she reached the Red Sea shores and walked along the beach up to Suez and then to Egypt.

Clearly there is some problem with this narrative. Through a thorough analysis of the manuscript we can easily find it out. Let’s jump directly to the conclusions. The codex found in Arezzo is not a full transcription of the original Egeria’s diary, but only a “collage” of excerpts, quoting the journeys outside Jerusalem made by the pilgrim during the three years of her sojourn in the holy city, assembled in a different order from the original.

From Valerius’ letter we know that the very first journey of Egeria was made to Egypt, where she followed “all the legs of the ancient peregrination of Israel…”(Cap.1). Only later, “burning for the desire to see the holy mountain of God” (cap.2), Egeria programmed a dedicated journey to mount Sinai.

In the manuscript the order of the two journeys has been inverted and they have been put in sequence in such a way as to make the Faran of Egeria coincide with the oasis of Feiran. In this point the copyist inserted the distance of 35 miles, which couldn’t be known to Egeria in this form, because that distance was expressed in Roman miles only in the VI century, when emperor Justinian established a garrison in Feiran and built a fortified monastery at the foot of Gebel Musa.

Evidence of this manipulation is shown at page 37 of the Codex Aretinus, where a footnote, written by the copyist, tries to fix some contradiction, yielded on the text by the operation of connecting in the wrong sequence two different journeys.

Thus, the only data in the manuscript, supporting the identification of Egeria’s holy mountain with the St Katherine, is devoid of any value.

EGERIA’S ITINERARY AT HAR KARKOM

Egeria’s diary is too precise, coherent and detailed to be a fantastic tale; it certainly describes a real journey in a real place. Let’s see then how it fits the area of Har Karkom.

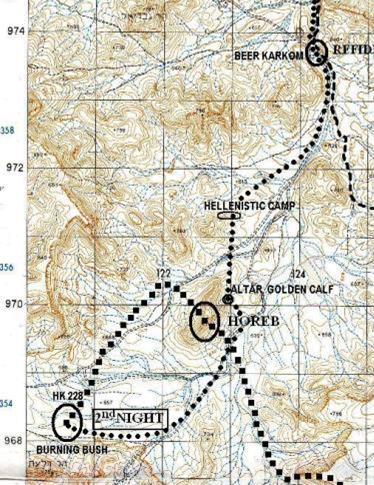

If we set all the information provided by the manuscript in the Har Karkom’s scenario, we are forced to follow an itinerary that matches completely, down the smallest detail, the data provided by Egeria.

1st day - From Beer Ada (Faran) to the site HK 183

The starting and return point of the itinerary is Beer Ada, a site at the confluence of wadi Karkom with wadi Faran, whit important archaeological remains of the roman-byzantine period. It’s an obligated choice, because Egeria left and returned back to a place named Faran.

She left on a Saturday, early in the morning, and went along wadi Karkom on a mount (probably a mule), together with some local guides, up to the entrance of Karkom valley. An easy track of about 20 km, that required no more than 6 or 7 hours, 8 at the most counting the breaks, to be covered.

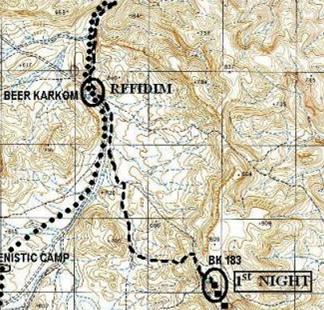

fig. 9 – The way from Beer Ada (Egeria’s Faran) to Beer Karkom, identified with the biblical Refidim, at the entrance to the God’s valley

In the afternoon she reached the well of Beer Karkom, at the beginning of wadi Karkom. In front of the well there is a small hill, with a seat-like structure on the top, identified with the place from where Moses watched the battle between Israel and the Amelkites. According to Valerius of Bierzo, Egeria climbed that hill.

Once down, she entered the valley of God. The narrative of the manuscript starts at this precise point, when she “came on foot to a certain place where the mountains, through which they were journeying, opened out … and across the valley appeared Sinai, the holy mountain of God.” Here she stopped to make a prayer, as it was the custom.

Then, late in the afternoon, she turned into a mule-track, perfectly preserved still today, which follows the southern side of the wadi, skirting an old cemetery, with about 90 tombs (site BK 428), 40 of which Hellenistic while the others are more ancient.

Fig. 19 – Some of the 90 tombs of an old cemetery (site BK 428) along Egeria’s track (on top of the picture). It can be identified with the graves of lust reported in the narrative

Further on the track runs near the four large platforms of site BK426, BAC period, and crosses site BK 430 were several Nabatean tumuli are standing. Egeria says that at the beginning of the track she came across the “graves of lust”, where the dead for the quails poisoning were buried, evidently identified with one or the other of these structures, or maybe with all of them.

Fig. 20 – The platforms of site BK 426, skirted by the path followed by Egeria (on the left). On the right the path after the tombs of lust.

The path “crosses the middle of the head of the valley” for a couple of km and after that it ascents along a slope that goes up directly to a narrow ridge, where there is a large settlement (Bk 183) that was certainly occupied at the time of Egeria. Along the path, half way up, there are several rock engravings of the roman-byzantine period, some of which representing mounted persons. One of them is particularly interesting, because it represents a person on a mount with a women’s saddle, hailed by two people on foot. Certainly an important woman visiting the site. Mere coincidence?

Fig. 21 – On the left Egeria’s path, that can be travelled all the way up the slope on a mount. On the right a rock engraving, half way up, which represents a high ranking person, mounted on a women’s saddle, hailed by two people on foot.

The mule-track leads to site BK 183, exactly on the ridge, separating the Karkom valley from the Paran desert, that can be regarded as a long and narrow extension of the plateau of Har Karkom. There is a large enclosure, surrounded by dwellings, one of which, with a suggestive orthostat on the wall opposite to the entrance, could be identified as the church of the community mentioned by Egeria.

Nearby the structures there is a basin of about 500 sqm, which collects all the rain falling on the top, and it’s covered with fertile soil with evident traces of ancient gardening.

Fig. 22 - Site BK 183, with a large enclosure, surrounded by dwellings and by a green basin, with evidence of ancient gardening. The picture on the right shows the structure that was probably the church of the community.

To go from the well to the hermitage on the ridge requires from one to two hours, according to the pace speed and the stops along the way. Perfectly coherent with Egeria’s account, who says that “she reached the mountain late on the Sabbath”and she “stayed there that night”.

fig. 10 – The path followed by Egeria on Saturday evening, in the scenario of Har Karkom (from Beer Karkom to the site BK 183)

2nd day – from site BK 183 to site HK 238

From BK 183 to mount Sinai (site HK 40)

“Early on the Lord's Day, together with the priest and the monks who dwelt there, we began the ascent of the mountains one by one. These mountains are ascended with infinite toil, for you cannot go up gently by a spiral track, as we say snail-shell wise, but you climb straight up the whole way”.

The meaning of these words can only be understood following the track. From site BK 183 the plateau of Har Karkom can be reached along a path that runs on top of the ridge and goes down three saddles, the last of which very deep. The ridge is narrow and therefore the path goes always straight up and down on steep slopes, until it reaches the plateau. From that point the path becomes smooth and can be followed again on a mount till the foot of the central peak of Har Karkom (site HK 40).

Egeria “arrived, at the fourth hour, at the summit of Sinai, the holy mountain of God, where the law was given.”

At a normal walking pace, the distance between site BK183 and the top of the central peak of Har Karkom can be covered in about two hours. Egeria walked at a slow pace, so it took about three hours to reach the peak, where she arrived around nine o’clock in the morning (the fourth hour for Egeria, according the Roman practice of dividing the day in 12 hours).

fig. 11 – The path on Har Karkom’s plateau, running from site BK 183 to the central peak, right in front, identified by Egeria with Mount Sinai, where the law was given to Moses.

The structures on top of Sinai

Once on the top, Egeria saw a “church, not great in size, for the place itself, that is the summit of the mountain, is not very great”. Egeria makes a large use of superlatives in every occasion, so that church must have been very small. Nowadays on that top there isn’t any roman-byzantine structure, but only a very recent tumulus, made up by some tourists utilizing the stones of an ancient semicircular structure, of about two meters of diameters, that could only have been dedicated to the cult.

When Egeria “arrived at the summit, and had reached the door of the church, the priest who was appointed to the church came from his cell and met us, a hale old man…and the other priests also met us, together with all the monks who dwelt on the mountain”.

The central peak of Har Karkom is bordered by the wadi that collects the waters falling on the plateau, to discharge them on the valley after about one km, with a spectacular fall.

Along the wadi, right at the foot of the central peak, there are two roman-byzantine settlements (sites HK 38 and Hk 39), which dwellers drew water from a puddle at the end of that same wadi (site HK 92).

A few meters from these dwellings, small orchards, still green today, were cultivated in the wadi’s bed, in perfect accord with Egeria’s words: “as we were coming out of the church, the priests of the place gave us eulogiae, that is, fruits which grow on the mountain. For although the holy mountain Sinai is rocky throughout, so that it has not even a shrub on it, yet down below, near the foot of the central height, there is a little plot of ground where the holy monks diligently plant little trees and orchards and set up oratories with cells near to them…

Later on, the monks showed Egeria “the cave where holy Moses was when he had gone up again into the mount of God”.

The cave was “shown” to Egeria, meaning that it was not on the same top. In fact the small cave indicated as Moses’ (site HK 42) is perfectly visible on top of a twin raising aside the main one.

fig. 14 – The small cave on site HK 42, indicated as the one where Moses hided from the God’s sight.

In this part of the itinerary the topographic characteristics, travel times, dwellings, orchards, monks and so on, match completely, down to the smallest detail, with Egeria’s narrative.

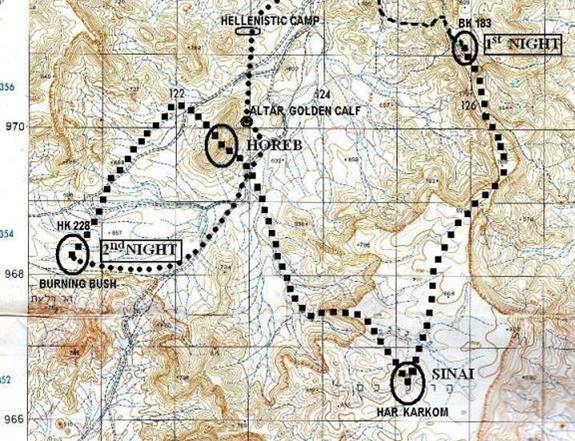

Moun Horeb (site HK 221 b)

A couple of hours later, around 11 o’clock, Egeria “began to descend from the summit of the mount of God and then she ascended to another mountain joined to it, which is called Horeb, where was holy Elijah the prophet, when he fled from the face of Ahab the king, and where God spake to him …”.

It took less than two hours for her to reach the top, where she stayed for at least one hour, starting to descend at about two o’clock in the afternoon, the Roman eighth hour (mount Horeb is separated from Sinai also in the St Katherine scenario, but it is impossible there to go from top to top in only two hours).

The description of what there is on that mountain is precise and detailed: “a church …and the cave where holy Elijah lay hid is shown to this day before its door …a stone altar also is shown which holy Elijah raised ”.Then she “came to another place not far off, where holy Aaron had stood with the seventy elders,… on a great rock which has a flat surface”.

This is the perfect description of an isolated hill, right at the center of Karkom valley, site HK 221b, with two large adjacent rocks on top.

On top of the largest of them looks there is a Hellenistic temple of 3 by 6 meters, and on its side a large shelter under rock; in front of the temple, at the end of the acropolis, there is a stone altar with steles. The smaller rock is separated from the first by a shallow saddle and it’s an ideal place from where to observe the acropolis.

fig. 16 –The stone altar on site HK 221b in front of the Hellenistic temple. On the right the flat rock where Aaron and the seventy elders stood

From mount Horeb to the burning bush

From site 221, Egeria’s mount Horeb, some roman-byzantine sites (BK 492, BK 506), with a clear structure of monk’s “laurae”, can be reached without problems in less than half an hour. From them, going south along the valley, one meets a series of roman-byzantine agricultural terracings (sites HK 225, 227), at the center of which there is an ancient settlement (site HK 228), with four large dwellings in a row, surrounded by several smaller ones, and a cemetery nearby, with a dozen of tombs. At the Egeria’s time this site had to be particularly luxuriant and it can plausibly be identified with the place at the “head of the valley, where there were very many cells of holy men and a church in the place where the bush is, which same bush is alive to this day and throws out shoots”.

Everything coincides with Egeria’s account, in particular distances and travel times. She says that she descended from mount Horeb in the afternoon at the eighth hour and arrived to the bush by the tenth hour (two hours before the sunset). Site HK228 can be reached with easy in a couple of hours from the top of HK 221, even taking into account short stops at sites BK 402 and 506.

Third day - from HK 228 back to Faran

The journey along the valley

Going back along the valley, from the settlement near the bush to the starting point, we meet some of the most extraordinary archaeological sites of Har Karkom, with the same characteristics described by Egeria. First, at the foot of site HK 221 (mount Horeb), a big altar (site BK 512) surrounded by steles, that deeply impressed her. We can realistically suppose that the monks identified it with the altar of the golden calf and that it was probably someone of them who put against it a stone shaped like an animal head, to make the identification more convincing.

fig. 19 – A biblical site (BK 512) mentioned by Egeria during her visit to mount Sinai: the altar of the golden calf, surrounded by steles. On the right an animal-like stone leaned against the rock perhaps by some ancient monk.

900 meters further north, in a small hidden valley, there is a very large encampment of the Hellenistic period, with more than 100 structures. Neither Egeria or her guides were able to date correctly those remnants, which of course were ascribed to the Jews, as well as a long list of other archeological sites that they met along the way to the valley’s entrance: platforms, tumulus, dwellings of different types and so on (sites BK 462, 463, 458, , 454, 450 etc.)

fig. 20 - A large Hellenistic encampment and a BAC structure in Karkom valley, perfectly fitting Egeria’s words: “they showed us where they all had their dwelling places in the valley, the foundations of which dwelling places appear to this day, round in form and made with stone”

At the end “the place also was shown to her where the tabernacle was set up by Moses for the first time”, that can be identified with two large rectangular prints on the ground.

Fig. 21 – On the left, the print of the tabernacle mentioned by Egeria. On the right, a recent hypothetical reconstruction of the tabernacle on that same print.

Finally she arrives, at the end of the morning, to the well of Beer Karkom, where she takes wadi Karkom and goes back to Beer Ada, in wadi Faran. Along wadi Karkom she meets several monks’ settlements (BK 503, 622, 628, 641), where she probably stops for a while to greet the dwellers and take some refreshment.

fig. 22 – Egeria’s itinerary, from site 228 to Beer Karkom, along the valley, where she met all sorts of ancient archeological structures

The travel times of the third day too are consistent with the narrative. From site HK 288 to Beer Karkom there are no more than 8 km, that can be covered with easy on a mount in three/four hours, counting short stops now and then.

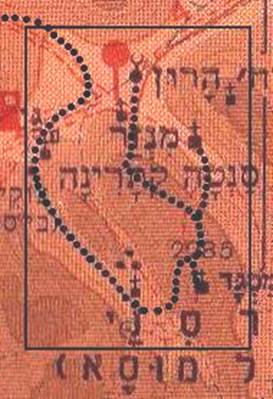

fig. 23 – The complete Egeria’s itinerary in the area of Har Karkom, showing the differences of altitude along each path, never higher than 200 meters, consistent with the travel times.

The rest of the day was enough to cover the 20 km from Beer Karkom to wadi Faran. A long and tiring journey, after which the pilgrim had to rest for a couple of days.

fig. 24 – The complete three days journey of Egeria from Faran to mount Sinai and back.

Conclusions

Travel times, description of environment, archeological sites, people living there and their dwellings, orchards and their location, everything in Har Karkom’s scenario fits to Egeria’s description. Every detail of her account, even her personal impressions, find a precise match in the diary, at such a point that it could rightly be regarded as the best tourist guide ever to Har Karkom, without any change. In fact, the tour described on the above maps, made in strict accord with the indications of the text, is the best possible to visit all the sites with some biblical interest in that area.

Of course this cannot be held by itself as evidence that Har Karkom was the biblical mount Sinai; but on the basis of Egeria’s account we can maintain with certainty that it was regarded as such by Christian pilgrims and monks during the first centuries of the current era, until its dwellers were wiped out by the Islamic invasion (which spared instead the St Katherine monastery).

Back to: Holy Mountain Project

[1] The ebionites were monks who lived in the desert in absolute poverty, and this is where their name probably came (ebion= poor)

[2] Information provided personally by Prof. Mariano Dellomo, responsible for the library of Montecassino. It is confirmed by the vast literature on the subject.