THE FLIGHT FROM HARAN

After twenty years Jacob fled from Mesopotamia to return to Canaan. He must have worked out a plan in advance, that would permit him to leave Haran without leaving behind the fruits of twenty years' work. There were two major obstacles to the realization of his plan. The first concerned Laban and his relatives, who certainly had no interest in allowing Jacob to take all that accumulated wealth out of Mesopotamia, and who would have done everything possible to prevent him from doing so. The second and by far more serious obstacle was Esau, who hated his brother. It was expected that he would try to avenge himself in some way or at least prevent Jacob's return to Palestine, where he would be able to claim the rights to Isaac's heritage. This was, in fact, the unsolved bone of contention between the two brothers.

The plan, that Jacob put into effect to avoid the first of these two obstacles, was simple and can be reconstructed precisely on the basis of the account. The plan was based essentially on the fact that Jacob could count on the protection of the Egyptians (evidently his mother interceded with them on his behalf). The concept, therefore, was to sneak quietly away, without warning, and reach the nearest Egyptian garrison before his father-in-law, who most certainly would rush after Jacob, could capture him.

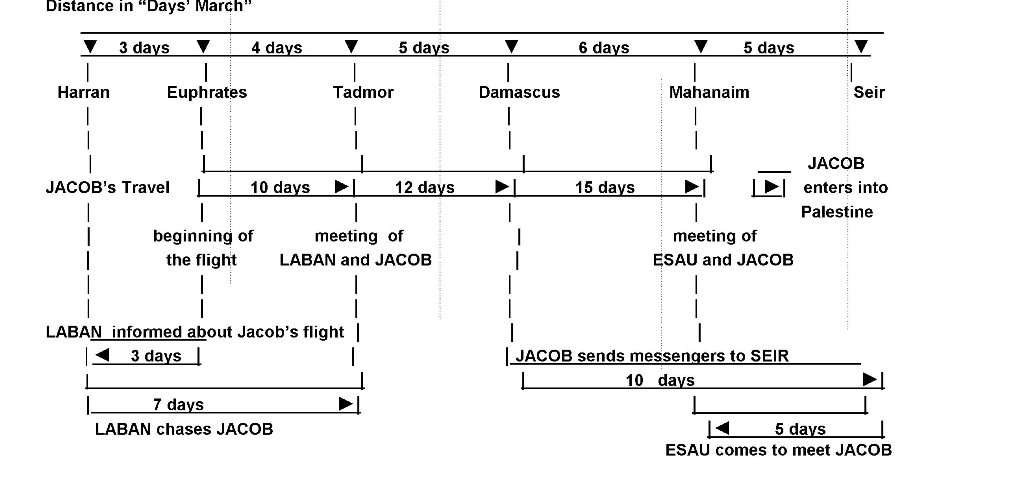

The essential factors for success were surprise and careful timing. To reach Palestine, Jacob had two options. He could go west to Karkemish, where he would have to cross the Euphrates by boat and then onto the track to Aleppo and Damascus, as Abraham had done long before. Or, he could turn south, and after three “days' march” from Haran cross over where the Euphrates was fordable, near Raqqah; he would then proceed along the track that joins Mesopotamia to Palestine, passing through Tadmor, the main center of Eastern Syria and known in Roman times as Palmira.

Having decided that he wanted to take all his livestock and servants with him, Jacob had no alternative; crossing the river by boat, with such a quantity of people and animals would have taken days and days. Since rapidity and the element of surprise were essential, he was obliged to take the Tadmor track. Throughout ancient times, but then more than ever, this city was an extremely important commercial center since it controlled a large part of the caravan traffic from Mesopotamia to Palestine and Egypt and vice-versa. Therefore, it had to be the site of a strong Egyptian garrison. If Jacob could reach it, he would be safe.

The main problem was that Tadmor was four “days' march” from the places where the Euphrates could be forded. This was a distance of about 150 kilometers (90 miles) that Jacob would have to cover quickly to prevent Laban from reaching him. Jacob, however, had a great handicap to overcome as he himself declares: “My lord knows that the children are tender and that I must care for the ewes and cows that are nursing their young. If they are driven hard just one day, all the animals will die!” (Gen 33, 13). He was forced to “proceed slowly, at livestock pace.” He could not, therefore, cover more than 15 kilometers (about 9 miles) a day, compared to the 35-40 kilometers (about 22 miles) in a normal “days' march.”

At that pace it would have taken Jacob not less than ten days to reach Tadmor. He had to ensure that Laban could not reach him before then. The Bible reports all the phases of the plan and the timing required for success. The fords at Raqqah are little more than a hundred kilometers (62 miles) from Haran where Laban lived--that is just three “days' march” exactly. Jacob had previously reached a spot near the fords and sent for his wives and children. Then, at dawn on a summer's day--the river at its lowest level, allowing the smaller animals to cross--he crossed the Euphrates and took the track towards Tadmor. “On the third day Laban was told that Jacob had fled. Taking his relatives with him, he pursued Jacob for seven days and caught up with him ... “ (Gen 31, 22). Of these seven days, it took three to reach the fords of the Euphrates; the remaining four took him to Tadmor.

The Bible states that he caught up with Jacob in the hill country of Gilead, east of the Jordan. This, however, is clearly a mistake because an analysis of the route establishes with certainty that both of them should have reached a point near Tadmor at the end of the tenth day of the escape (see table at fig. 9). But before Laban could grab his son-in-law, he had a visit: “God came to Laban the Aramean in a dream at night and said to him, 'Do not say anything to Jacob, good or bad.’” This was certainly the commander of the Egyptian garrison of Tadmor, who must have received precise instructions from Palestine as to how he should proceed in these circumstances. The fact that he appeared “in a dream” to Laban means, as we have noted in other circumstances, that he sent a written message.

Laban presumably had started out with the intention of taking the fugitive back, or at least of retrieving a large part of the goods stolen from him. We can deduce this from Jacob's resentful words: “If the God of my father, the God of Abraham, and the Fear of Isaac had not been with me, you would surely have sent me away empty-handed. But God has seen my hardship and the toil of my hands and last night he rebuked you.” (Gen 31, 42).

In the face of the Egyptian injunction, Laban could do no more than make the best of a bad situation. He protested, he made charges, he lamented the behavior of his son-in-law, he claimed the restitution of his “terafim,” but finally he resigned himself: “The women are my daughters, the children are my children and the flocks are my flocks. All you see is mine. Yet what can I do today about these daughters of mine or about the children they have born? Come now, let's make a covenant (...) 'Mind: if you ill-treat my daughters or if you take any wives besides my daughters, even though no one is with us, remember that God is a witness between you and me (...). Early the next morning Laban kissed his grandchildren and his daughters and blessed them. Then he left and returned home.” (Gen 31, 43-44 and 31, 50-55).