JACOB IN MESOPOTAMIA

Jacob arrived in Haran and followed his parents’ instructions to choose a wife from among his uncle Laban’s daughters. The details of his meeting with Rachel on the outskirts of the city are given in Genesis 29 2-12. This story is a “love at first sight” classic, and justifies the preference, which according to the narrator, the Patriarch showed for the younger of his two wives. It is the type of anecdotal love story that popular fancy loves to dwell on, often embellishing the facts with fanciful details. This particular story relates events that probably happened quite differently or in another epoch. When Jacob arrived in Haran, in fact, Rachel could not have been more than six to eight years old.

“As soon as Laban heard the news about Jacob, his sister's son, he hurried to meet him. He embraced him and kissed him and brought him to his home and there Jacob told him all these things. Then Laban said to him, 'You are my own flesh and blood!' Jacob stayed with him for a whole month. After this Laban said to him 'Just because you are a relative of mine, must you work for me for nothing? Tell me what your wages should be.' Now Laban had two daughters. The name of the elder was Leah and the name of the younger was Rachel. Leah had weak eyes, but Rachel was lovely in form and beautiful. Jacob was in love with Rachel and said, 'I'll work for you seven years in return for your younger daughter Rachel ' (...) and Jacob served seven years for Rachel ...” (Gen 29, 13-30).

The story goes on, describing how Laban, after seven years had passed, tricked Jacob into marrying Leah, the elder daughter, and after seven days Jacob married Rachel, his favorite, too. The account seems credible and there is no reason to doubt it, except for one detail, which is of extreme importance for reconstructing the period of time of Jacob's sojourn in Mesopotamia; this is the period of Jacob’s service spent before his marriage to Leah.

According to the quoted account, Jacob married Leah only “after” having served for seven years. This is unlikely since normally, in this type of transaction, the son-in-law's service for his father-in-law is effected after the wedding. In fact, if it were effected beforehand, the future father-in-law would have no means to compensate the would-be son-in-law in case something happened in the meantime to the betrothed daughter. Furthermore, as long as the girl was of marriageable age, it made no sense to defer the wedding, thereby delaying without reason the essential duty of every good wife: bringing children into the world. Additionally, in Leah's case, an analysis of the dates of her children's births during the twenty years' sojourn in Haran makes clear she could not possibly have married Jacob after seven years.

In reality Jacob must have declared to Laban the reason for his journey immediately upon his arrival in Haran and negotiations were therefore begun at once. Having reached agreement, the wedding was celebrated without further delay. It must have taken place at the end of the first month of his stay; it makes no sense to mention a month’s stay in Haran, if it had not been followed by an important event. Seven years later Jacob also married Rachel, for whom he served Laban an additional seven years.

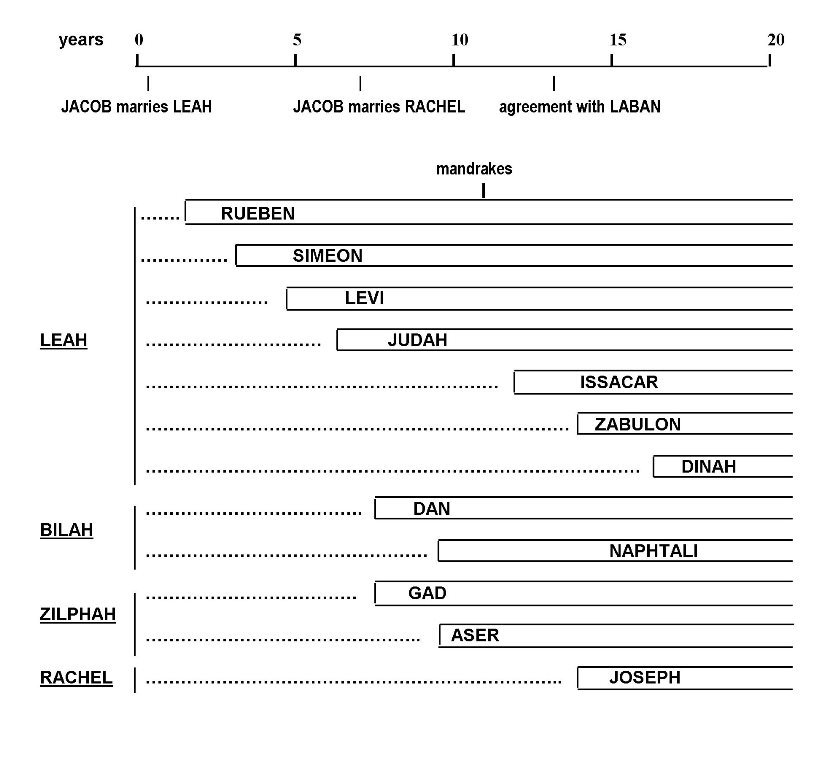

A precise analysis of the sequence of his children's births demonstrates incontrovertibly that Jacob wed Leah immediately upon his arrival in Mesopotamia (see table at fig. 8). Joseph, the eleventh of Jacob's sons, was born to Rachel exactly six years before he left Haran; it was then, in fact, having terminated the fourteen years' service for his wives, that Jacob asked Laban to let him go (Gen 30, 25). Before Joseph was born, Leah gave birth to six sons and probably one or two daughters. The Bible cites only male births, and it must be presumed that statistically a certain number of females were born, although they were not even mentioned unless they were involved in some important event. The only exception, in fact, is Dinah, Leah's daughter, who is only mentioned because she played an important role, albeit passive, in the destruction of Shechem (Gen 34).

If Leah had wed seven years after Jacob's arrival, she would have had just another seven years in which to bring all those children into the world, which is simply not credible. It becomes even less so when we consider another episode which has great importance in determining the chronology of this period. Genesis 29, 35-30, 17 states that a few years passed between Leah's fourth son, Judah, and her fifth, during which Bilhah’s two sons, Dan and Naphtali, and Zilpah’s two sons, Gad and Aser, were all born. After Issacher, Leah had Zebulon, who was older than Joseph.

Even admitting that the time between one birth and the next could had been be very brief, we cannot accept that Issacher was born after Jacob's twelfth year in Mesopotamia. It is just not possible that Leah was married only five years previously. It is even less so, since Issacher was born following a curious episode--a sort of barter agreed upon with Rachel, who conceded to Leah a night of love with Jacob in exchange for a few mandrakes (Gen 30, 14-18).

Leah's firstborn, Reuben, picked these mandrakes exactly nine months before Issacher was born, and, therefore, not later than the eleventh year. At the time of this event Reuben must have been at least eight or ten years old, since it is very unlikely that a younger child would roam among the fields picking roots. This proves beyond all doubt that Leah wed Jacob immediately upon his arrival in Haran and not after the end of the seventh year.

Rachel, however, is a different question. The story of her substitution during the first night, unbeknownst to Jacob, is suspect to say the least. It is unimaginable that Jacob could be so unaware that he did not notice an exchange of the girls; and it is even more difficult to think that Laban could count on such ingenuousness, that his deceit would not be discovered until the morning after. The whole account is unbelievable. What is more probable on the other hand is that Rachel was too young for marriage, and that Laban and Jacob had reached agreement, in the meantime, on a marriage with the elder daughter; after seven years he would also wed Rachel, who by then would have reached the appropriate age. An analysis of the successive births of Jacob's children after Judah offers us confirmation in this regard.

At the moment of Rachel's wedding, Leah had already given Jacob four sons; it is easy to understand Rachel's anxiety about having a son as soon as possible. But she became pregnant with Joseph only thirteen years after Jacob's arrival in Haran. This fact, besides constituting a further indication in favor of the theory that Rachel was wed at least seven years after Jacob's arrival, offers a reasonably reliable criterion for defining the period in which Jacob's other children were born.

Rachel must have decided to introduce her maidservant Bilhah into her husband's bed (Gen 30, 3), only when a certain period of time had elapsed after her wedding and without any sign of pregnancy--at least a year. Therefore, Dan, Bilhah's first son, must have been born at least twenty months after Rachel's wedding, or about nine years after Jacob's arrival in Mesopotamia. Bilhah's second son, Naphtali, was born soon following, perhaps twenty months after Dan.

According to the sequence given in Genesis 30, Leah's maidservant Zilphah gave birth to both sons, Gad and Asher, after Naphtali, at the end of the eleventh year. If this is true, it means that Leah also must have decided to put her maidservant Zilphah into her husband's bed, only after Bilhah had become pregnant with Naphtali. Therefore, Gad must have come into the world a few weeks or months, after Naphtali was born. Asher, Zilphah's other son, came along at least a year after Gad. Issacher and Zebulon, Leah's last two sons, arrived between Asher and Joseph; therefore, Issacher was born immediately after Asher, and Zebulon a short time before Joseph.

The sequence above could be accepted without reserve if it were not for the fact that, in Genesis 49, when Jacob gives his blessing to his sons he names them in a slightly different order: Dan, Gad, Asher and Naphtali. This order seems more likely than the first one and is to be preferred. In fact, Leah must have decided to get her husband to make her maidservant Zilphah pregnant as soon as she found out that Rachel had done the same with Bilhah. Therefore, Gad must have been born just after Dan. The “contest” with the maidservants must have gone on for some time afterwards, and in the end Leah won by a short lead. Therefore, Asher must have preceded Naphtali by only a very short period of time. So, between the tenth and fourteenth year, Jacob had no less than seven of his twelve sons, coming in this order: Dan, Gad, Asher, Naphtali, Issacher, Zebulon and Joseph.

Dinah must have been born a couple of years before the departure from Haran. It may be that among Leah’s first four sons, there were one or two daughters not mentioned in the Bible. Similarly, other daughters could have come into the world between Judah and Issacher and between Zebulon and Dinah. We can also presume that some daughters were born to Jacob's other wives; so when he left Haran he must have had about twenty children of both sexes.

From the foregoing analysis it turns out that when Jacob arrived in Haran, Rachel was a child of six or eight years of age. At about fourteen she got married. She gave birth to Joseph when she was about twenty-one. Seventeen years later Joseph was sold by his brothers in Egypt (Gen 37,2). Benjamin was born in the same year (see Part III, chapter 11, “Jacob in Palestine”) when his mother was near forty. This was a rather advanced age for child bearing, especially after a long period of infertility--so much so that physiologically the woman could almost be considered a primipara, with all the risks this entails. And, in fact, Rachel died giving birth.

This late pregnancy is consistent with the family's history. Among the women of the house of Tareh, a gynecological characteristic appeared with a certain frequency, which rendered pregnancies difficult in the younger women yet more probable in those approaching menopause. In fact, Sarah became pregnant with Isaac shortly after the onset of menopause. Also, Rebekah only became pregnant after twenty years of marriage. Thus Rachel, in spite of the attentions of her husband, who was more in love with her than with his other wives, had her first child only after seven years had passed, and had the second seventeen years later.

Leah, on the other hand, was undoubtedly very fertile; she gave birth to her first child after just nine months of marriage and she continued to procreate without interruption for almost twenty years, terminating her lucky “career” with Dinah, who was probably born just before leaving Haran. We deduce that Dinah was Leah’s last, born after Zebulon, not so much from the order in which she is cited--since Dinah was female, order is not to be considered--but more from the episode for which she is known, the destruction of Shechem. When Shechem, son of Hamor, the chief of the city, took and raped her, she was certainly of marriageable age and so could have been no more than about fifteen.

At that time Joseph had already been sold in Egypt and, therefore, at least eleven years had passed since Jacob's return to Palestine. We can deduce this from the fact that when Joseph was sold by his brothers, they were grazing their flocks near Shechem: “Now his brothers had gone to graze their father's flocks near Shechem, (...) so Jacob sent Joseph off from the Valley of Hebron to Shechem.” (Gen 37, 12-14). This indicates that the city had not yet been destroyed. Following its destruction, in fact, Jacob had to leave the area definitively in order to avoid a vendetta by the neighboring populations (Gen 34, 30). It is quite unlikely that his sons would return to graze their flocks in the vicinity, thereby exposing themselves to severe reprisals.

Therefore, the destruction of Shechem took place some time after the kidnapping of Joseph, and Dinah was born during the last four years of the sojourn in Haran, if not later. Since Leah also was about fifteen years old when she married Jacob, she must have been at least thirty-five when her last daughter was born.

There is no indication as to where and when Leah died. In spite of the meager consideration the compiler gives to her, she is a figure who stands out in the biblical story. The unfortunate girl with the listless eyes had a strong personality and did her duty in silence and contentment, in spite of the humiliations to which she was subjected. She gave birth to at least seven children, two of whom carried the greatest weight in the future story of Israel: Levi and Judah. She gives an impression of great solidity and reliability, particularly in contrast to the fragility of her beautiful younger sister. Jacob, at least according to the story, does not seem to have shown any particular signs of gratitude towards her, but it is certain that he owed her much, and without her his life would have taken a very different course.

In particular, Leah must have given him useful advice and support in his relations with Laban. The economical agreements between the two men are reported in a very simplistic manner. Once again the popular relish for anecdotal stories took precedence over objectivity and precise information. The affair of the “ringstraked, speckled and spotted cattle” (Gen 30,39) is given great space. The result is a confused mix-up from which it is difficult to establish the exact terms of the agreement between the two men.

It seems that the question of recompense for Jacob's work was controversial and the object of frequent arguments between them. “You changed my wages ten times ...” (Gen 31,41), Jacob rebukes Laban on Mount Gilead. This is a sign that the agreement between them was not clear and definitive, and in any case disliked even by Laban's other sons, who were not happy about the intrusion of an outsider such as Jacob. Perhaps it was also for this reason that Laban rushed after his son-in-law, because he did not consider that the purloined livestock were Jacob's by right, and he hoped to recoup at least some of them. Jacob, probably with a guilty conscience, went away furtively without even saying good-bye.

It seems worthwhile to estimate, even if it must be roughly, the wealth Jacob accumulated during his twenty years in Haran. According to the Bible (Gen 31, 41) he was compensated only during the last six years, since during the first fourteen, having to pay for the two wives, he served without remuneration. But in reality it is more likely that Jacob had begun to accumulate wealth as soon as he arrived there. There must have been a provision in the marriage contract indicating that he would take care of his father-in-law's affairs, but presumably he would have been permitted to look after his own too.

Jacob's pretensions were very modest at first, and Laban and his sons accepted them with pleasure. Jacob was thereby able to take over the administration of Laban's property and goods without encountering any resistance or excessive suspicion. Once the fourteen years of more or less free labor had elapsed, he took advantage of his position and the fact that he had become virtually indispensable, to make some rather weighty requests, which Laban must have considered excessively onerous. With proposals and counterproposals, promises made and retracted, arguments and so forth, the affair dragged on for six years until Jacob left, taking with him all that he considered his by right.

It was no doubt an enormous fortune. We can get an idea from the inventory of livestock he sent a few weeks later as a gift to his brother Esau: “Two hundred she goats and twenty he goats, two hundred ewes, and twenty rams, thirty milk camels with their colts, forty kine, and ten bulls, twenty she asses, and ten foals.” (Gen 32,14-15). This was a total of almost six hundred head of livestock! To these must be added any losses during the journey and the gifts he had to make to Tadmor and later to Mahanaim for protection and free passage. Recall also that Jacob excused himself for not following Esau to Seir, by pointing out the slowness of his livestock (Gen 33, 13); we must presume that in spite of these losses he still had a large number left.

So we come to the conclusion that the riches Jacob accumulated in Haran are to be valued in thousands of head of livestock, large and small. And for the care and defense of these, he must have had at his service on the order of hundreds of servants, together with their families--a true and proper tribe!